Every year, over seven million deaths worldwide for tobacco use. Hundreds of thousands of people affected by illness related to smoke.

Numbers that could be compared to the losses caused by drug use around the world. However, while Drug control policies have been implemented in the last decades, governments still don’t consider the fight against smoke as a priority. Why?

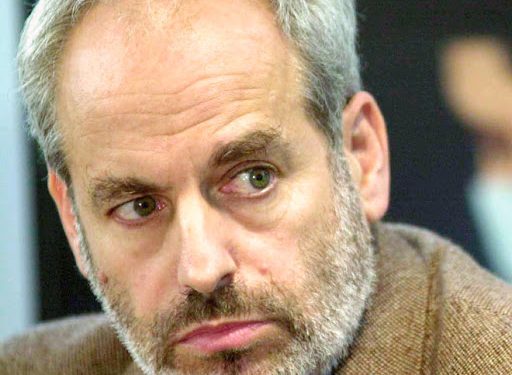

We discuss the topic with Dr Alex Wodak, President of the Australian Drug Law Reform Foundation. Expert on Harm Reduction, he supported establishing the first needle syringe programme and the first controlled injecting centre in Australia and worked in developing countries on HIV control among people who inject drugs.

-Dr. Wodak, for over twenty years you were the Director of the Alcohol and Drug Service at St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney, Australia. How did it change Drug control policies over the last thirty years?

I was the Director of the Alcohol and Drug Service at St Vincent’s Hospital for 30 years (1982-2012). Soon after I began my appointment, the epidemic of HIV began in Australia. My hospital was in the national epicentre of the Australian epidemic as it was located close to the largest population of groups at highest risk. The largest drug market in the country for the last half century was also located in that neighbourhood. So an urgent priority in the early 1980s was reducing the spread of HIV among and from people who inject drugs. Fortunately, there was a national high political level agreement in April 1985 to adopt harm minimisation as the official national drug policy. ‘Harm minimisation’ was later defined to mean the combination of supply reduction, demand reduction and harm reduction. It was also agreed that policies would cover alcohol, tobacco, prescribed and illicit drugs. This commitment still exists although the enthusiasm for harm reduction fluctuates over time and is stronger for some drugs than others. The National Tobacco Strategy includes a commitment to the combination of supply reduction, demand reduction and harm reduction but the enthusiasm for tobacco harm reduction is minimal. Although Australia is not a major country it has more international influence in health policy than expected for its population size. Australia was an early adopter of tobacco control policies aiming to reduce smoking rates. Inevitably this involved tackling the enormously powerful tobacco industry. Smoking rates began falling earlier and faster than many other western countries but smoking rates have only fallen slowly in recent years despite very vigorous tobacco control policies. Cigarette prices are now the highest in the world with nine tax increases in the last ten years. The Australian Health Establishment is strongly opposed to tobacco harm reduction. There is a vigorous debate about vaping with restrictive policies in force. Yet attempts to make these policies even more restrictive were defeated twice in 2020. Australia is the only Western country that requires a doctor’s prescription for nicotine used for vaping. There are 21,000 smoking related deaths per year in a population of 26 million. For the Australian Health Establishment, defeating Big Tobacco seems more important t than reducing smoking related deaths as fast as possible.

–Judgment among policymakers is that smoking isn’t as dangerous for societies as drugs use is. Do you agree? Why?

Poor policies for illicit drugs have worked well politically for a long time. But the days of a War On Drugs approach is coming to an end. Unfortunately tobacco policy has been a specialised area quite separated from policy for other psychoactive drugs. As in many other countries, policies regarding illicit drugs were often close to zero tolerance while policies for legal drugs were often relatively permissive. There have been many arguments over the years. Keeping a focus on the actual harm caused by drugs and drug policy has always been a struggle. Each new form of drug harm reduction was fiercely resisted but almost all were eventually accepted. So methadone treatment, needle syringe programs, drug consumption rooms and many other new strategies resulted in vigorous debates. After some years it was recognised that these new strategies were very effective, produced few adverse effects and were also cost effective. I expect that this will also be true after some time for all the new forms of tobacco harm reduction.

-Drug Control policies hang between prohibition with harsh law enforcement and a human rights-based approach. Which are the “best practises” Tobacco Harm Reduction should follow to be effective?

Many valuable lessons were learnt in the battle to reduce HIV infection among and from people who inject drugs. Public policy must be based on the best scientific knowledge at the time, even if this knowledge is inevitably always somewhat incomplete. Policy that threatens the human rights of populations always has a high public health cost. Policy has to be based on the world as it really is rather than a utopian world some might dearly wish for. Public policy works best if support can be achieved from across the political spectrum. People most at risk of the new health threat must play a meaningful role in developing and implementing policy. Policies have to be communicated simply, clearly, repeatedly and consistently to the community. These lessons apply as well for tobacco as they do for illegal drugs such as heroin.